PAMAMA

ᜉᜋᜈ :

Heritage, Inheritance and Legacy

Pamana

1935-1986

Pamana II

1986-2000

Pamana III

2000-2009

“The story of the Filipino's community life in the Pacific Northwest can be likened to a sentimental ballad, a prayer-chant, if you may, that has waited for so long to be sung.

Through more than half-a-century of attempting to weld a community life in the beautiful city of Seattle, the Filipino expatriate has struggled, sacrificed and pursued with determination his vision of a meaningful existence in a strange new land.

Wide-eyed and packing dreams, they arrived. As they labored to make those dreams unfold, they in turn shaped the character of the developing Filipino community.

This book attempts to capture what are rooted in the past as well as to present inspiring events in our time.

And because the number of Filipinos with first-hand accounts of the early years continue to dwindle, it would indeed be a monumental omission by the community-at-large if their stories and recollections are not preserved. Not only to educate future generations of Filipinos but, more importantly, to secure these priceless historical records of our forebears. Equally significant would be the challenge of the present: how the Community now stands fifty years after a bunch of cold and homesick Filipinos got together one autumn day in 1935 to organize themselves into a cohesive and lasting group.”

C.N. Rigor

Seattle/April 1986

For Pamana

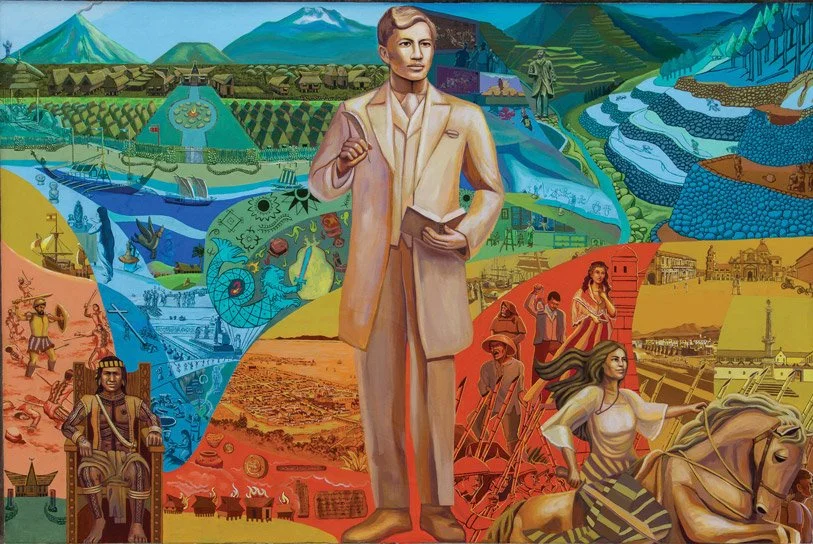

Mural by Eliseo Art Silva

The present and future of the Filipino Community of Seattle

Panel 1 – The Filipino Story: Our Golden Ages (900AD – 1565 and 1821 – 1900)

The Early Settlers

The Filipino Community of Seattle saw its humble beginnings when American shipping lines brought into the port of Seattle hundreds of Filipinos during the early ’20s. Many of these Filipinos came from the Hawaiian Islands. The great majority, mostly students, came to the United States to further their studies. Those who found the educational and employment opportunities suitable to them decided to remain in Seattle while others proceeded to other parts of the country. Those who remained found employment in Alaskan canneries, in railroad gangs, and in the farmlands of the state of Washington.

It was not long before Filipino entrepreneurs came to the scene. The first of these business entities was the Luzon-Visayas-Mindanao Corporation, known as the L.V.M., Inc. for short. The L.V.M. was under the presidency of Valeriano N. Sarusal. The corporation established an employment agency, a restaurant, a barbershop, a pool hall, ran a hotel, and operated an agency for steamship companies. It also secured a license to subcontract for the various Alaskan canneries in order to give employment to the many Filipinos who were coming to this part of the country.

Other Filipino-owned enterprises were the Manila Corporation and the Philippine Eastern Trading Company. These companies were likewise designed to go into the contracting and subcontracting business for Alaskan canneries and to maintain an inventory of supplies that the Filipinos needed. Pio De Cano was the president of the Manila Corporation. Prominent among the contractors and subcontractors were Valeriano N. Laigo, Emiliano Sibonga, Vicente Agot, and Pedro Santos. Filipino restaurants, barbershops, and even a dry goods store were established.

Mostly Catholics by birth, the first Filipino club was soon formed by early Filipino settlers. Under the guidance of Mr. L. J. Easterman, an attorney who was very interested in the welfare of Filipinos, the Filipino Catholic Clubhouse was organized and used to house Filipino students who were attending high schools and colleges in the city. The clubhouse served both the spiritual and social needs of the Filipinos. Weekly meetings were held and national holiday celebrations were always considered important events in the clubhouse. It was within this atmosphere and mood that community spirit was fostered. Among those who played important parts in the lives of the Filipinos during this period were Dr. Jacinta Acena, now a practicing physician back in Baguio, Philippines, and Professor Victorio C. Edades, who is now with the faculty of the University of Santo Tomas in Manila.

Students at the University of Washington who aspired for intellectual nourishment besides that provided by the Filipino Catholic Clubhouse organized their own Filipino Club. It was in 1925 under the guidance of Mrs. Jane Garrott that the Filipino Club of the University of Washington was founded. It was the objective of this club to have interracial meetings and to encourage sympathetic understanding of national and international issues. Speakers of various nationalities were invited to dinner and chatted informally with the members after each program.

In 1925 Manuel S. Rustia, then commercial attaché of the Philippine government in Seattle, published a newspaper, The Philippine Seattle Colonist, to serve as the voice of the local Filipino community. Mimeographed and issued twice a month, the Colonist waxed eloquent on political issues concerning the Philippines and militantly stood for the rights of the Filipinos in the United States.

The paper was edited by Lorenzo L. Zamora, and the editorial cartoonist was Victorio C. Edades.

This then was the Filipino Community of Seattle in the early part of the ’20s. While others tried their luck in other states, thousands chose to settle down in Seattle. Many were attending high schools and colleges. There was a community newspaper. There were employment agencies, restaurants, barbershops, pool halls, hotels, and even a grocery store, which was owned by Valeriano N. Laigo. One could see that it was teeming with activity. Every Filipino seemed prosperous. They had ample resources, and they rented the newly built Eagles Auditorium for two nights in 1926 to commemorate the anniversary of the martyrdom of Dr. José P. Rizal. A Filipina, Nene Encarnacion, reigned as queen during the festivities. One had to wear formal attire in order to get into the ballroom.

Events That Preceded Incorporation

In 1927 Victorio A. Velasco, a student, suggested to Vincent O. Navea, then the president of the University of Washington Filipino Club, that a building should be purchased to be used as a students’ clubhouse. He further suggested that in order to attain this, Filipino businessmen in town should be approached for their support and cooperation.

The suggestion was accepted and a committee was created to seek support from businessmen. A fundraising campaign was organized. The group appointed Vincent O. Navea as Chairman and Victorio P. Velasco as Vice Chairman. An aggressive campaign was planned for the Alaska canneries during the fishing season under the sponsorship of the University of Washington Students’ Clubhouse. At the end of the season, the Committee was able to collect a sizable amount.

Before resuming the campaign in 1929, however, the Committee felt that the drive for funds would have a better chance of success if the name of the sponsoring organization was changed from the University of Washington Students’ Clubhouse to the Seattle Filipino Community Clubhouse. The intention was to dispel the notion that only the students were to benefit. So, to ensure the support of a wider sector, the fundraiser’s name was changed to the Seattle Filipino Community Clubhouse, and the organization was subsequently incorporated on April 20, 1933, in the state of Washington. Signers of the Articles of Incorporation were: Valeriano N. Sarusal, Vincent O. Navea, Johnny Dionisio, Sr., Urbano Canasel, G. R. Perez, Pio De Cano, Valeriano N. Laigo, and Eugenio P. Resos. The Board of Trustees chose Pio De Cano as president and Vincent O. Navea as vice president.

Under this new set-up, the campaign for funds continued. Every notable Filipino enthusiastically supported the drive. No stone was left unturned until a substantial amount of money was raised and turned over to the Board of Trustees.

By the early ’30s, various organizations in Seattle had sprung up like mushrooms. Regional, civic, religious, and fraternal organizations appeared on the scene. With all these diverse groupings, it seemed difficult to visualize the Filipinos as a unified ethnic group. But the true test came when the Philippines inaugurated the Philippine Commonwealth Government in Manila on November 15, 1935. The Filipino community wanted to celebrate Philippine Commonwealth Day on the same day that it was celebrated in Manila. So, a meeting of representatives from all organizations in Seattle was called. The delegates at this meeting agreed to form a new organization. They agreed to call this organization the Philippine Commonwealth Council of Seattle, which was to hold a two-day Philippine Commonwealth Day celebration.

During the election that followed, Pio De Cano was elected president, and Rudy Santos was elected vice president. Victorio A. Velasco was elected secretary, and Mamerto Ventura was elected treasurer. Members of the Executive Council were: Tel I. Baylon, Guido Almanzor, Vicente O. Navea, Prudencio P. Mori, Salvador Lazo, Julius B. Ruiz, and Johnny Maala. A constitution and a set of bylaws were drafted and approved. The two-day celebration was a resounding success. At long last, a new era had arrived—Filipinos in Seattle had finally become united.

For the next ten years, the Philippine Commonwealth Council of Seattle became the center of activity in the city’s Filipino community. It planned and launched the annual celebration of Commonwealth Day and the annual commemoration of Rizal Day. But when the Philippines was granted independence on July 4, 1946, the name Philippine Commonwealth Council of Seattle was no longer appropriate, and a change became necessary. The Filipinos adopted a new name: the Filipino Community of Seattle and Vicinity. A new constitution and a set of bylaws were drafted and approved, and the organization was again incorporated under the laws of the state of Washington.

But in 1952, in anticipation of the third wave of Filipino immigrants entering Seattle, another change of the name was made. It was recognized that by keeping the word Vicinity as it was carried in the original name, the task of administering to the needs of the organization was much more difficult. Besides, Seattle, by itself, is already a large community. So, the name Filipino Community of Seattle—minus the word Vicinity—came into being. Its constitution and bylaws were amended to reflect this change, and what we have today is the Filipino Community of Seattle, Incorporated.

History of the Filipino Community of Seattle

by: E. V. Vic Bacho

PAMANA I

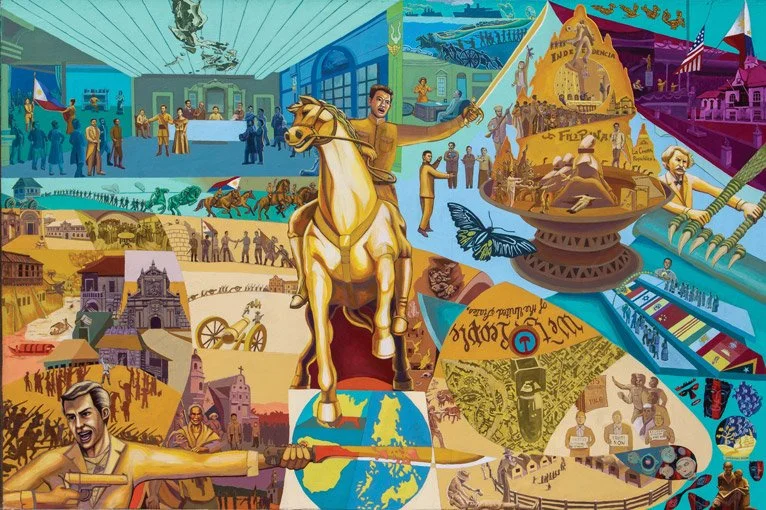

Mural by Eliseo Art Silva

The present and future of the Filipino Community of Seattle

Panel 2 – The Filipino Story: Our Declarations of Independence (1898-1913, 1904-1946 & 1972-1986)

There has always been a Filipino community of Seattle. Yes, even before its formal establishment as an “umbrella” organization in 1935, which changed the small “c” in community to a capital “C.”

Hopefully, there will always be a Filipino Community of Seattle—notwithstanding whining detractors and power-hungry secessionists who are ever present to negate all the good works, good intentions, and oft-times foibles of its hard-working officers, stalwart members, and supportive constituents for the last 60 years.

This is not to say that The Filipino Community of Seattle, Incorporated, always has been perfect. Of course not. What human organization is? The fact of the matter is Filipino Americans (Pinoys, as the community founders called themselves) have attempted, struggled, achieved, and, in a host of other ways, failed to do their job under the aegis of the corporate umbrella. Nevertheless, Seattle has had and continues to have “The Community.” Ours.

After all, what is a community by way of a Pinoy definition? As has been said, get two Pinoys together and they have a community. That communal sense of pakikisama was already in evidence with the first Filipino social club in 1870 in New Orleans as a hallmark of the First Wave of Filipino Immigration to the U.S. from 1763 to 1906.

In the State of Washington, the Filipino community could have started with the arrival of an adventurer by the name of “Manilla.” Not lingering in Seattle, he opted instead to work in a sawmill at Port Blakely on Bainbridge Island. His documented arrival was in 1883—six years before Washington became a state in 1889. It is believed he was among other Filipino sawmill workers.

In 1903, the steamship Burnside docked in Seattle with a crew including 40 Filipinos. The crew was engaged in laying telephone cables connecting Alaska to the U.S. mainland. After their three-year U.S. government job was done, it is reported these Pinoys stayed in Seattle to become its first residents during the era beginning the Second Wave of Filipino Immigration to the U.S. from 1906 to 1934.

Of course, Seattle’s first Filipino American family moved to Seattle in 1909. Its matriarch was Rufina Clemente Jenkins from Bicol—a war bride of the Spanish-American War and married to an African-Mexican American sergeant, Francis Jenkins. They had four children—the oldest born in the Philippines and the rest in various U.S. Army posts—and have descendants now bordering on the sixth generation in Seattle.

Thus began, 86 years ago, the Filipino “community” in a family way—that is, if two births are also counted among other Filipinos—namely the 50 Bontoc having been exhibited in the “Igorrote Village” of the Alaska-Pacific Exposition in 1909 on the University of Washington campus.

Some 150,000 Filipinos—men, women, and children too—left the Philippines for the U.S. between 1907 and 1930 to become the pioneering Filipino Americans… Pinoys. Seventeen were counted in the State of Washington in 1910. By 1920 there were 958 Pinoys; by 1930, 3,480.

In Seattle, the Pinoy cluster sprang from the Jackson/King Street/Chinatown area to First Hill and Cherry Hill, with St. James Cathedral, Maryknoll, the Filipino Methodist Church, the Church of the Immaculate Conception, and Providence Hospital as the neighborhood landmarks.

Contrary to academic myths perpetuated by so-called “authorities” of Filipino American history, including naïve university professors, the Seattle Pinoy community—like all other dense clustering of Pinoys elsewhere in the U.S.—boasted of students, women, families, children of the Second Generation (with some even in the Third), professionals (especially women in nursing), university degree-holders, lodges, businesses (with women entrepreneurs, yet), newspapers, church groups, socials, sports and recreation (gambling in particular) in a supposedly stereotypical bachelor-oriented, common-laborer society.

Of course, Seattle, being on the edge of America’s Far West, topped by hardy territorial Alaska, was an emerging frontier town when Pinoys began to arrive in larger numbers during the 1920s and 1930s. The Pinoy community endured more than its share of blatant racism, failures, and poverty, coupled with violence in the forms of internecine murders, shootings, stabbings, fights—let alone police harassment, searches, and more bigotry.

But through it all, in good times and bad, the Seattle Filipino community (small “c”), the Filipino Community of Seattle (capital “C”), and Filipino Americans survived and attained measures of achievement in their own way—etched with a dignified work ethic in the Filipino American Experience—to give a legacy of a stable Pinoy Community to their children and to those who followed in the succeeding Third Wave of Filipino Immigration to the U.S. from 1945 to 1965 and the Fourth Wave since 1965.

Unlike another community, Seattle also was in possession of a Pinoy-dominated union that served as an economic opportunity for men, plus students, to work in the Alaskan salmon canneries. From this cannery-farmworkers union (actually there were two at times) came Seattle union leaders to lead the Community, and union members, who came from throughout the U.S., to help contribute substantially to the financing of the long-held dream of a Community clubhouse.

The term “Filipino Community” is Pinoy-originated, meaning it is an American coinage with organizational implications. Early Filipino American pioneers of the Second Wave, by the 1920s, invented this Pinoy phenomenon of “Filipino Community” to resolve their mutual needs within a formal organization made up of their kababayans and spouses and governed by a constitution and/or charter with duly elected officers.

In the case of the then-Filipino Community of Seattle and Vicinity, Incorporated, its 1946 charter mandated all “to promote and protect the interest of Filipinos; to cultivate unity and cooperation among all Filipinos; to foster and establish better relations and sympathetic understanding between Filipinos and non-Filipinos; to encourage a unified observance of Philippine events of national or historical importance; to provide members with facilities for wholesome recreational, social, educational, and cultural activities; to foster and instill civic spirit and cultural pride among Filipinos; to coordinate with the city, county, state, and national officials in all matters affecting the welfare of Filipinos…”

Our Community, blessedly, has been fortunate in having leaders of vision for more than 60 years.

Although the Filipino Community of Seattle began to develop informally in existence as a viable ethnic enclave as early as 1926, its formal organization did not take shape until the Philippine Commonwealth Executive Committee, under the chairmanship of Pio De Cano, first met in 1935 in the Strand Dance Hall at 6th Ave. S. and S. King St.

Unity was the concern then, as it still is now.

The Community’s pioneering leaders believed that in achieving that unity two priorities were uppermost in their minds: a central organization and a clubhouse.

The first priority was to establish a “central community organization” which would “serve as an ‘umbrella’ organization for all Pinoy clubs, lodges, associations, societies, and other special-interest groups within Seattle.”

Thus, on November 15, 1935, was established the Philippine Commonwealth Council of Seattle with 300 members and De Cano its first president.

This 60th anniversary celebration acknowledges that unincorporated Commonwealth club as the root of the formal establishment of the Filipino Community of Seattle, Inc., and De Cano, a powerful contractor and lodge chieftain, as the Community’s first president.

After the Commonwealth of the Philippines assumed its independence to become a republic, the Philippine Commonwealth Council became the Filipino Community of Seattle and Vicinity in 1946.

Its present Washington State corporate title as the Filipino Community of Seattle, Inc. (“FCS” or “FCSI”) became effective in 1952.

The Community In Seattle

by Dr. Fred Cordova, Filipino American National Historical Society

(Editor’s Note: The author wrote the following article for the souvenir program of Seattle (FCS) as it marked its 60th Anniversary on December 15, 1995. It is reprinted here in full.)

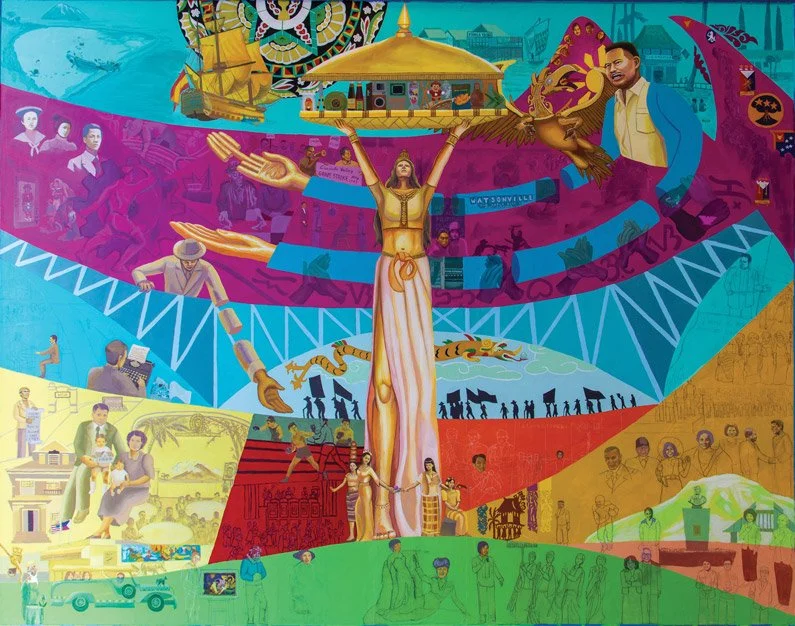

PAMANA 2

Mural by Eliseo Art Silva

The present and future of the Filipino Community of Seattle

Panel 3 – The Filipino American Story: Bridging Our Generations and Humanizing Our Workers (1587-1965)

Congratulations to the Filipino Community of Seattle on its 75th anniversary in 2010. Over the past 75 years the Filipino Community of Seattle, Inc. has gone through many changes. However, before there were official organizations - there was a Filipino community in Washington State with a small"c." It began in the late 1880s with the trickling in of Fillipino men working in lumber mills, laying telephone cables from Seattle to Alaska in 1906, and the 1909 arrival of Sgt. Frank Jenkins and his war bride Rufina Clemente Jenkins at Fort Lawton. This first group of Filipino Seattleites grew to include servants of returning Americans, students (pensionados and self-support-ing), U.S. Navy enlistees, men seeking work and adventure.

After the Spanish American War all Filipinos (male and female) who became American "nationals" were allowed to come to the United States without passports - if they could pay their boat fares. However, few women came during those early years. The ratio in Washington State was one Filipina for every thirty men. Since most men were single when they arrived, this resulted in an early community with a number of interracial marriages and the creation of a"bachelor society" which would last until the 1950s.

The 1920s were days of prosperity. Old photographs show" old timers" at social events - men, young and handsome in American-made wool suits or tuxedos, while women were dressed in lovely ternos from the Philippines. There are photos of families with children, newly formed regional clubs or fraternal lodges.

The concept for a clubhouse began in 1927 when Filipino students at the University of Washington, under the leadership of Victorio A. Velasco and VincentNavea, approached Filipino businessmen to help purchase a building they could call their own - to gather in fellowship. The beginning of a clubhouse is part of my family history. My father, Valeriano M. Laigo, was one of the Filipino businessmen who donated to that fund.

To gain greater public support, in 1929 the Committee changed the name of the sponsoring organization from the University of Washington Students' Clubhouse to the more encompassing Seattle Filipino Community Clubhouse. The Great Depression also began in 1929 - and the project to raise funds slowed considerably as America experienced a devastating economic crisis which lasted throughout the 1930s. Yet, unemployed Filipinos survived through the generosity of extended families and organizations.

Most Filipino bachelors lived in Chinatown or with families on First or Cherry Hills. This proximity created a true sense of family and community. They needed each other to counter the daily discrimination they faced.

In 1935, Congress passed the Tydings-McDuffie Act. Filipinos changed from American "nationals" to " aliens." Immigration was reduced to 50 a year and the Philippines became a Commonwealth. To celebrate the Philippine Commonwealth inauguration on November 15, 1935 local Filipino clubs met to plan a two-day celebration. During the meeting the Philippine Commonwealth Council of Seattle was formed. Pio De Cano was elected president, Rudy Santos vice-president and Vic Velasco became Secretary. In 1946, this organization became the Filipino Community of Seattle and Vicinity.

World War Two brought more changes. Most Filipino men enlisted in the 1st and 2nd Filipino Infantries trained in California and became American citizens before deployment to the Philippines. This allowed them to bring their" war brides" to America - into a close-knit community. Washington Hall, Finnish Hall, and the Seattle Chamber of Commerce Auditorium were sites of frequent dances, family parties, queen contest tabulations, and formal banquets.

Filipinos from other communities - Wapato, Bremerton, Bainbridge and farm areas in the Green River Valley - often attended these events. Queen contests with teenage daughters of pioneers helped build up the clubhouse bank account. The annual Filipino Community 4th of July picnics at Seward Park's Pinoy Hill drew thousands of Filipinos to share food and camaraderie, to participate in games, and to promise "See you here next year."

By the 1950s, Bataan-Corregidor survivors who gained American citizenship before the Philippine independence in 1946, arrived with families. The community was growing. New arrivals became part of the Community and gradually assumed leadership roles. After years of dreaming and saving, the clubhouse became a reality in 1965 when an old bowling alley was purchased.

Filipinos in Greater Seattle finally had a home.

In late 1960s, the Philippine Consulate began celebrating June 12th as Philippine Independence Day - inviting only heads of different organizations. This created a social strata of the "ins" and "outs."The annual 4th of July Philippine Independence picnics slowly died out. Many "old-timers" and their second-generation children felt disconnected to the community they nourished and helped build for many years. The fight for civil rights, open housing, affirmative action and immigration changed the demographics of Filipinos.

The 1965 revision of immigration laws brought thousands of new Filipinos to Washington State. They lived everywhere. Most didn't know the others. Farm areas became towns or cities with their own Filipino communities. Churches - both Catholic and Protestant - had strong Filipino organizations which often did not use the Filipino Community's building.

Yet, today there is a new synergy in the Filipino Community of Seattle. The beautiful expanded Filipino Community Center facility has become a source of pride for many. Once male-driven, today women often initiate new activities. After many years, it is reaching out to the young. The torch of change has been passed on again - as it has so often the past 75 years.

A Brief History of the Filipino Community from the 1880s to the Present

by Dr. Dorothy Laigo Cordova, Executive Director, Filipino American National Historical Society (FANHS)

PAMANA 3

Mural by Eliseo Art Silva

Panel 4 – The Filipino American Story: Lifting Our Stories Through Art, Thus Transforming the

US Cultural Landscape to Reclaim our Human Face on the Philippine Sun (1965-2022)